Manuel Troike talks to the Swiss ethnomusicologist Dr. Thomas Burkhalter about his music documentary Contradict – Ideas for a New World. Together with Peter Guyer, Burkhalter gives six musicians from Ghana a chance to speak, to look at the changing values of our time from the African continent, and to show how trends, ideas and visions are increasingly decentralised in a globalised world.

[Download PDF-Version] | [Abstract auf Deutsch]

Manuel Troike: Thomas, you squeezed so many questions into the 90 minutes of your new music documentary Contradict, I initially was really overwhelmed and did not know what to ask you first. You showed issues of gender equality, health service, ecology and climate action, colonization, music production, and democratic expression. All these topics we discussed during the last days of our conference and we will discuss tomorrow. Thank you very much for the insight into these very inspiring music scenes which you captured. Could you give us a brief introduction to how you got to the topics and musicians of Contradict? What were your approaches and aims for this project? I read that you had started already in 2013 with a short film about Ghana and the FOKN Bois and then came back later to finish the documentary?

Thomas Burkhalter: It was basically a long-term project. I had known the FOKN Bois, Wanlov The Kubolor and M3NSA for a long time. They did an amazing hip hop musical film in 2010 called Coz Ov Moni. I invited this film and the two artists to the Norient Film Festival in 2010. So, I got to know them. Not only that, but I really found their work very strong. I had already been thinking of doing a documentary about music in different cities in the world, and it now turned out to become that in this documentary the FOKN Bois would play a big role. We ended up in Ghana with this long-term project between 2013 and 2018. We went there four times.

Manuel Troike: Doing a documentary in a different cultural area is always difficult. What was your approach for doing it with Peter Guyer? How do you start in Ghana where you do not know many people besides the FOKN Bois?

Thomas Burkhalter: It was definitely a challenge, and I think working in Africa has become more challenging in recent years. There is this movement by local artists that challenges European filmmakers, or academics, when they write about Africa or African cities because they would like to represent themselves and wish to not be represented through the eyes of white male filmmakers like us. This discussion was always there for me, also it has been a key discussion for many years. When we met the FOKN Bois and when I got to Ghana, I became the traditional ethnomusicologist. You know, the person who loves to be in the field to meet as many people as possible. I have done a lot of internet research and had a long list of artists. Peter and I started meeting many of these artists, discussing their work, even did some podcasts with them. There was a lot of work without camera before we started filming.

As you said, there were many questions. We wanted to avoid giving a traditional image of Africa. We were very careful when shooting in the streets not to bring forward too many stereotypical images. This question and many others were crucial for the documentary.

Manuel Troike: What was the most fascinating or surprising thing you learned throughout your journey in Ghana?

Thomas Burkhalter: That is an interesting question. I think the most fascinating thing was the editing. It took us many months – about two years I think, almost. Peter and I edited a lot. We wanted to put as many levels as possible in this film, and it is not a traditional structure. We had many people telling us there are too many people and topics in this film. But Peter and I felt it would be better not to get rid of all these levels. In the end – as I hope – it works because if you take one scene out of the film, it falls apart. It is like big magic sometimes. It is fascinating. You really do not know why. So, this was the biggest challenge for me because of the fieldwork aspect, meeting, and interviewing people, I had known for many years.

The other very difficult aspect was interviewing these evangelical priests from the mega churches. Normally, I do interviews with artists of whom I think that their work is outstanding, and I want to learn from them. But this was the first time in my career that I interviewed someone who is basically a thief. I conducted this 90-minute interview with about five bodyguards around him and pretended to be fascinated by him. It gave me like a one-week depression afterwards because I felt like being dishonest. You cannot talk to someone without really saying what you are thinking. It was like an ‘Ali G move’: You pretend to be very interested in the powerful and hope that they say difficult, challenging, or strange things. But it is a role that I do not like.

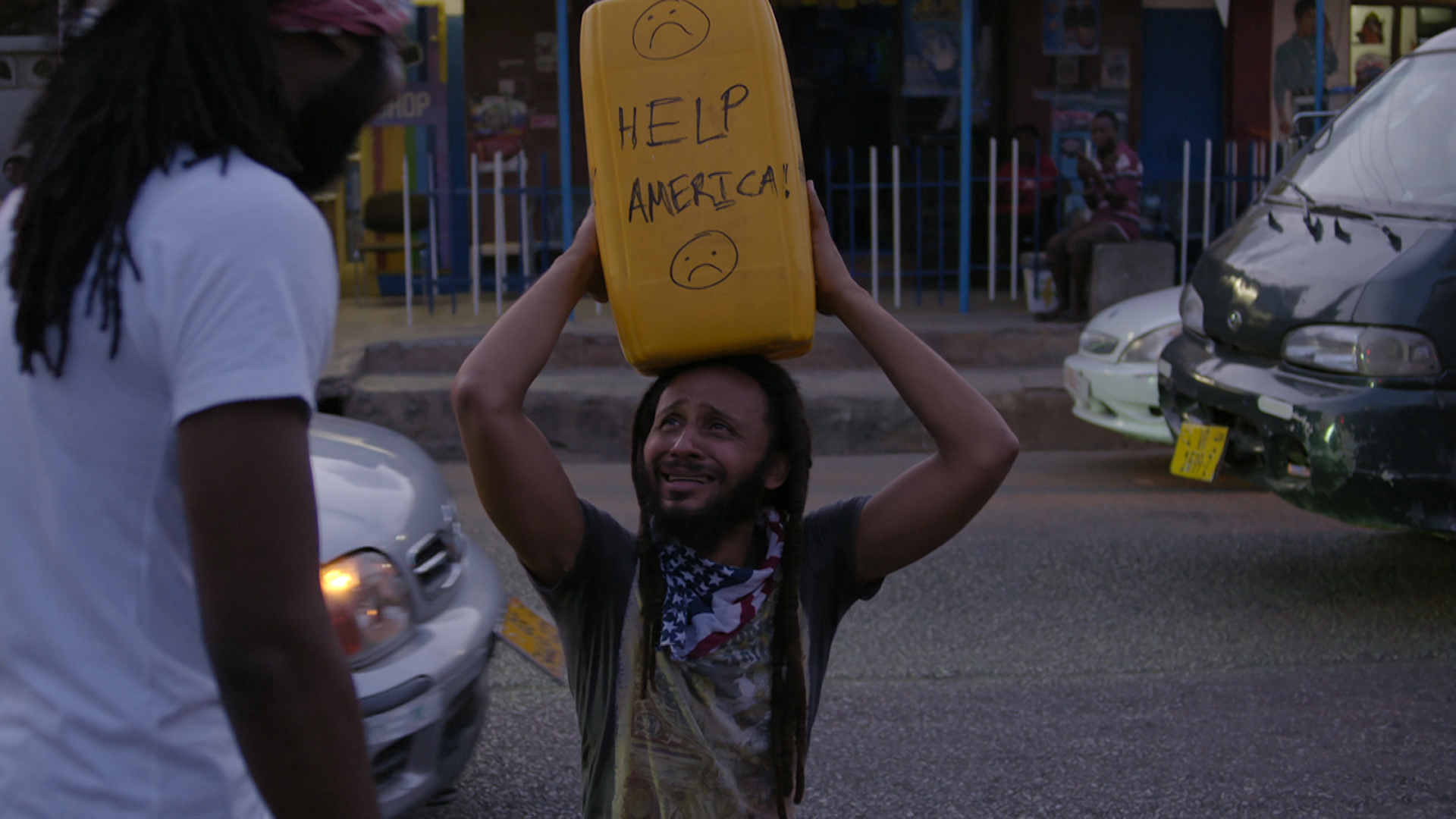

Manuel Troike: I would like to come back to this a bit later because the religious dimension to me seems very fascinating. For me, one of the most blatant contradictions you showed us in this film was the FOKN Bois performing “Help America” and raising money and awareness for the poor people in the USA. At first glance, this seems more than absurd. If you listen to the protagonist throughout the film, they are talking about Ghana having everything they need, and you could get an insight into the minds of the FOKN Bois. Thomas, could you please tell us a bit more about the motivation to this song and scene?

Thomas Burkhalter: This was a song that already existed, and they did not have a video clip, and so Peter, Balthasar Jucker (the sound engineer) and I used the music video to test out working together. I cannot tell you for sure what the musicians’ motivation for the song was. They are intelligent musicians with deep lyrics. But in a country like Ghana there are many artists who feel that Africa is not less important than nations on other continents, and that the world is changing. And of course, it is a provocation to a certain extent. It has many levels, but it is not fun and speaks about a lot of dreams and frustrations.

Manuel Troike: During the film we get to know other musicians like Adomaa, Worlasi or Akan who all tried to express their point of view or their utopia through music. Their home studios did not look so much different from those most of our own students here in Paderborn/Germany have. The video equipment they use is up-to-date and rather professional, which you can see especially in the drone scene in the Savanna Mountains. Popular music is often attributed with being an instrument of democratizing in the sense of articulating and distributing opinions, as the initial hurdles regarding knowledge and technical equipment are very low. Would you say that what you captured in Contradict is an example par excellence for the democratizing elements of popular music?

Thomas Burkhalter: Definitely. It was essential for us to show them in their studios. It is not only another film about Africa. It is a film about a new generation that is coming up, about a world that is changing. Maybe they have less amount of hardware than you would find in a Swiss music studio, but they have a lot of software and plugins – bought or cracked. They are trying to succeed. Democratization sounds nice, but to succeed and to be/become? heard is another story. With the changing algorithms of for example Facebook or Spotify, it is somewhat frustrating sometimes. Many people are producing remarkable songs, but no one really hears them. A lot of them are trying hard to move forward, and that is what I like about the artists. They are real hard workers. It is not just fun. It is the idea of creating a new career path. Outside these studios, there are so many young people who are so frustrated and angry because they have no possibilities. In Ghana, there are many people without jobs, they have a high and rising suicide rate. So, producing music is a possible but not easy career path.

Manuel Troike: In one of the features on your homepage, you interviewed John Collins who said: “The white congregation are turning towards Black Churches in Europe, and the African missionaries are going to bring Jesus to the primitive whites, the savage whites. It is a complete inversion… Now the Africans are going to bring humanity to Europe in the form of religion and the form of music” (Pepperell n.d.). Would you say that this is also the case with popular music? What can we learn from the Ghanaian musicians you met in terms of creativity, music production and songwriting? To stay in the religious speech: Do we need a new evangelization of Western popular music?

Thomas Burkhalter: I do not know if evangelization is the term I would use, but I think the pop world has changed and will be changing. There are more and more players outside the USA and Europe for sure and a lot of them are stars and very successful. I think the Top 40 will be less Euro-American in the future. There is a lot of talent out there and many hard-working people to get these voices up.

Manuel Troike: Near the end of the film, Wanlov talks about colonization and the effect on African music. Through protestant hymns they were forced to use Western tonality, and now they try to recollect to traditional African sounds and music. Do you see this as a possibility in a globalizing music scene, or is it even necessary to go back to the roots?

Thomas Burkhalter: I would never ask a Swiss musician to make music with an alphorn or push him*her into a certain direction. I think a good or interesting artist is not happy with initial results and is always trying to get a step further. There are many discussions about music software and DAWs being Westernized and that they prefer Euro-American templates and scales. I think within these pieces of software you have still a lot of possibilities. I personally work with Ableton Live and you can basically do everything you can think of. Maybe I am a bit naïve, but when you use all these possibilities, you can create a unique sound. If it sounds African or not is not the most important question to me. It is for sure interesting to do research, and collect sounds, field recordings or scales and use them in your music. But if you just put in an African instrument in a fast and superficial way, I am not sure if this really is something that makes music more local. I think locality is deeper than scratching the surface with these sounds.

Manuel Troike: I would like to go back to the religious topic which I already mentioned at the beginning of our talk. M3NSA says, “How different is being a rapper from being a preacher? You go on stage, get the mic, say creative things, say funny things, interesting things, tell stories, and the audience claps for you” (Pepperell n.d.). The musicians had a very ambiguous view of religion – especially those preachers, angels, and bishops you showed during the film. Is there any oppression for those musicians who criticize them? I could not get my head around that during the film. How is this music received in older generations in Ghana?

Thomas Burkhalter: In a way one could say that Ghana was a good place to film this documentary because Ghana is a quite stable country with a working democracy. It was not very difficult to film there. I never heard of death threats or something similar to critical artists. I think the frustration for these artists is that they can protest everything, but nothing changes. It is nice and open on the surface, but the power is distributed in closed circles. Wanlov regularly gets invited to TV and radio stations and says many provocative things, but he said he sometimes feels like a Clown. It is nice to have him there to show how open-minded you are and that you listen to everyone. But no one reacts to his opinions. That is also part of the frustrations they carry around.

Manuel Troike: To get to this topic a bit deeper, I would like to show a short clip which closes your documentary:

Manuel Troike: Throughout the film you are giving hints on a very special topic: mental health, depression, resignation. We can see this mostly as Mensa declares his resignation and stopping of political music in the radio show. But also, in scenes where depression shall be cured by religious rituals. You can really feel their struggling, their fighting with the political situations, religion and society. Maybe you had contact to the musicians the last days? How does Covid-19 affect them and their musical expression?

Thomas Burkhalter: It is a difficult time. But first I have to say some words to the clip you have shown. Poetra Asantewa is a really strong spoken word artist and she did not want to be in the film with pictures. She was the first that saw the rough cut, and the questions that she is posing at the end of the film are like her commentary on it. We wanted to have a part of the narration in the hands of someone from Ghana.

To come back to Covid: I am in contact with the artists, but Covid is a bit of a taboo topic. Anyone is annoyed by it. I am sure it is not easier than before. To be honest – it depends on my mood – but most often it is a bit of a sad film because when you travel you meet so many talented people out there who work hard to be successful. But creating content is not valued so much in this world. In Ghana, it is even worse. As an artist, you must be rich or excellent at promoting and networking. You can see it in the film as the rapper Akan talks about his WhatsApp group he introduced to be independent. But now the people in there are calling him in the middle of the night to get information about the next gig. It is crazy.

Manuel Troike: We talked about this topic a few minutes ago with Bettina Kohlrausch. We ended with questions about the existence of utopias in our modern world. What would you say: Do these musicians do have a utopia to change the world, or is it more or less a resigned scene you captured in this film?

Thomas Burkhalter: I doubt that these musicians are resigned. Again, creativity will never die. People want to create and say things – that is about being a human-being. The problem is how to reach other people with this work and not to get lost in the monopoly platforms that decide about. One solution would be to create networks and communities supporting each other, to share content outside these algorithms. We are in a competitive time and even people who are close to each other do not always support each other, because they disagree on a detail for example. We can disagree about our research, but we should not stop supporting each other because of little differences. We must support each other as well as possible. Norient as a platform tries to do this. We are trying to support other content and not only our own papers and music. Without these networks, we are completely dependent on Amazon or Spotify.

Manuel Troike: Most of us know a lot about Norient, but could you tell us about your work at Norient? What were your aims in founding this platform some years ago?

Thomas Burkhalter: When I founded it in 2002, I had different aims. It was like a small blog. It was an attack on World Music with Norient being a wordplay against Orientalism. It was important to me to talk to people about their musical works. Today, it is more like a platform that wants to bring together scholars, journalists, and artists. It shall be multidisciplinary. In a way, we hope that we can manage that Norient survives in a long term. We are working more and more with people from outside of Europe who curate content on the platform. To be honest, it is a constant struggle. We are pleased at the moment, but we are always fighting not to die. We have no structural funding and are not attached to universities. It was mostly our passion keeping us alive for the last 20 years.

Manuel Troike: I would like to ask you one last question, Thomas. As a person working in the intersection of academia, music production, journalism, and media production: What role do you wish Popular Music Studies shall play in the transformations we talked about? What do we have to do to help these musicians with their utopias?

Thomas Burkhalter: First, you have to keep up the good work. Keep researching, keep reading, keep writing. Secondly, I would like to encourage you to not be satisfied with publications in academic journals. Try to speak to a broader audience because I feel that these topics that we deal with are very relevant. What we can do with Norient is trying to translate academic articles into shorter pieces which are more likely to be read by others. Please do not hesitate to connect with Norient, so we can work together to get our content out in the world. We discuss important topics other people have to know about. That is why the Norient Film Festival is maybe our most successful project. People come to these cinemas to see the partially academic and ethnographic films, and through them they get new thoughts about today’s world. They get inspired. We should not do compromises to only release superficial work but try to find ways to bring the strong thoughts out of our work to other people outside our academic bubble.

On the Authors

Thomas Burkhalter, Dr., is an ethnomusicologist, interdisciplinary artist, and music journalist from Bern. He is founder and director of the international platform Norient – Performing Music Research (norient.com), the Norient Film Festival (NFF), and the Norient Space „The Now In Sound“ (2020). He co-directed the documentaries „Contradict“ (2020 – winner Berner Musikpreis) and „Ghana Controversial“ (Al-Jazeera Witness, 2019), the AV/theater/dance performance „Clash of Gods“ (2018) and is author of the academic book „Local Music Scenes and Globalization: Transnational Platforms in Beirut“ (Routledge).

Manuel Troike, M.A., is a research assistant in the „Popular Music and Media“ study programs at the Department of Music at Paderborn University. He is doing his PhD on technical and musical practices of mobile DJs in Germany and researches and teaches in the fields of Electronic Dance Music and DJ culture with a focus on mobile DJs and music programming.

List of References

Pepperell, Martyn. n.d. “Dancing in the church: Religion in Ghana”. Accessed September 13, 2021. https://www.contradict-film.com/feature-2-religion-in-ghana.

Proposal for Citation

Burkhalter, Thomas and Manuel Troike. 2022. „Contradict – Ideas for a New World. A Talk between Thomas Burkhalter and Manuel Troike about the Documentary Film Contradict.“ In Transformational POP: Transitions, Breaks, and Crises in Popular Music (Studies), edited by Beate Flath, Christoph Jacke and Manuel Troike (~Vibes – The IASPM D-A-CH Series 2). Berlin: IASPM D-A-CH. Online at http://www.vibes-theseries.org/burkhalter-troike-contradict.

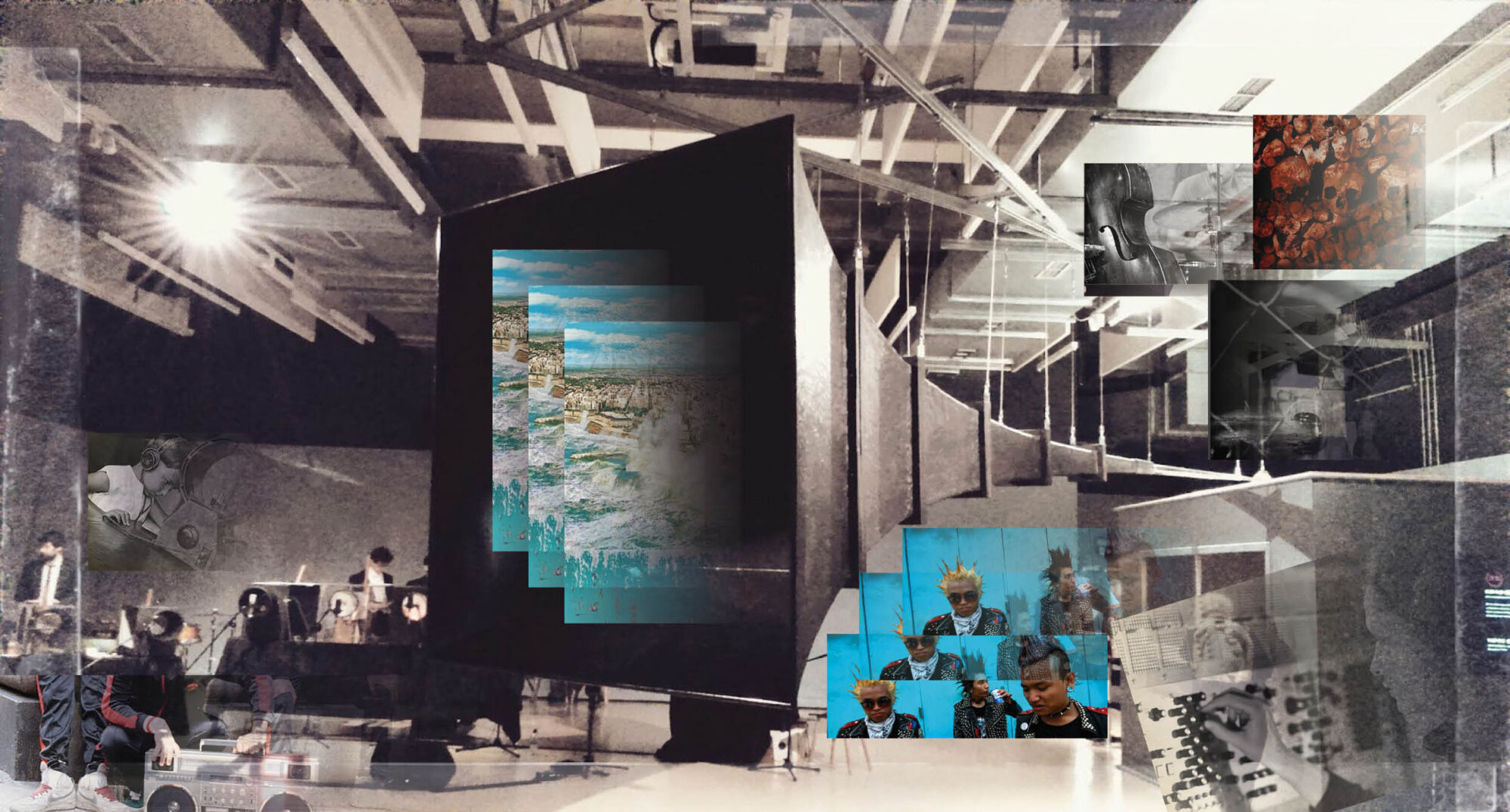

Cover Picture: Contradict (Film Still)

Abstract (German)

Manuel Troike führt ein Gespräch mit dem Schweizer Musikethnologen Dr. Thomas Burkhalter über dessen Musik-Dokumentation Contradict – Ideas for a New World. Gemeinsam mit Peter Guyer lässt Burkhalter sechs Musiker*innen aus Ghana zu Wort kommen, die den Wertewandel unserer Zeit vom afrikanischen Kontinent aus betrachten und zeigen, wie in einer globalisierten Welt Trends, Ideen und Vision immer dezentraler entstehen.